Teaching the history of America’s Black press

By Beth Hatcher

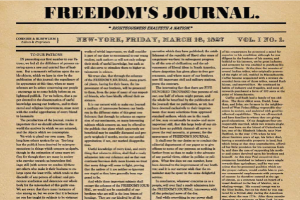

1827 — Freedom’s Journal, America’s first Black-owned and operated newspaper, began publication.

1852 — The African Methodist Episcopal Church established The Christian Recorder, the oldest continuously published Black newspaper in the United States.

1952 — Simeon Booker Jr. became the first Black reporter for The Washington Post, famously penning midcentury pieces on the nation’s civil rights movement.

Trevy McDonald — UNC Hussman’s Scheer Term Associate Professor — reels off these dates rapid-fire, from memory, as she details the timeline of a UNC Hussman course shining light on a critical aspect of Black history: the Black press.

McDonald, who also serves as and the school's director of ABIDE (Access, Belonging, Inclusion, Diversity, & Equity), teaches “MEJO 342: The Black Press and United States History,” which examines the foundations of Black media from the 19th century through the civil rights movement.

“We look at U.S. history through the lens of the Black press. I contextualize what we’re studying with looking at what was going on in the country with regard to economic, technological and political forces at that time,” said McDonald, who has taught the class since 2013.

From the abolition of slavery to the push against civil rights-era segregation, the course explores the voice Black press gave to African Americans, whose stories were often excluded from mainstream media, McDonald said.

“The Black press was founded on advocacy,” McDonald said. “It was very important for African Americans to have an avenue to share their experiences.”

However, the story of the Black press itself is also under-told, said Professor Emeritus Harry Amana, who helped create the course at Hussman in 1980.

“I’ve always believed that there’s a necessity for Black publications,” said Amana, who started his journalism career writing for the 1880s-founded Black newspaper The Philadelphia Tribune. “News about African American history is just one piece of the larger puzzle of American history, and it’s important for everyone to learn.”

Student Clay Morris ’23 agreed. “Knowing Black history is knowing American history,” said Morris, who said he’s drawn to any course that examines the intersection of Blackness with culture and history. The “MEJO 342” course has taught Morris a broader understanding of the foundational role the Black press has played in Black culture, and given him details he didn’t know, such as the debate at the time within the Black community about the pros and cons of Black Americans voluntarily leaving the country for Africa and Canada before the Civil War.

Pictured below, left to right: Pioneering late 19th and early 20th century investigative journalist Ida B. Wells, a little boy selling The Chicago Defender, a Black newspaper, in 1942, and Simeon Booker Jr., who became The Washington Post's first Black reporter in the 1950s. Pictured above, at right, a copy of Freedom's Journal, America's first Black-owned and operated newspaper. Photos courtesy of the New York Public Library Digital Collections and the Library of Congress.

Amana said the role of the Black press was foundational both internally and externally, noting that Black media outlets connected Black Americans to information within their own communities while also providing history’s first draft of life in America for the Black community.

Amana observes that to this day, coverage by the Black press of everything from the reporting on lynchings in the 19th century to stories on the struggle for civil rights help to contextualize modern issues like the Black Lives Matter movement and critical race theory controversies.

Student Anna Deaton ’23 appreciates the history she’s learning in the course.

“Learning about the history of the Black press is important for everyone because it demonstrates how important it is for marginalized individuals to have a voice and not be silenced,” Deaton said. “This history shines a light on the injustices that Black individuals in the United States faced.”

The course’s timeline, which also covers flourishing points of Black history like the Harlem Renaissance, culminates with a project that pairs students to examine a civil rights event. Students then write a paper and prepare a presentation about the event.

“One fascinating person that I learned about was Ida B. Wells,” Deaton said, referring to the trailblazing Black investigative journalist in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. “[Wells] was never covered in my previous history classes, and her involvement in the civil rights movement as well as the feminist movement was extraordinary.” (The Ida B. Wells Society for Investigative Reporting has been based in the school since 2019 with the mission to increase and retain reporters and editors of color in the field of investigative reporting.)

“Our students benefit tremendously by deeper insight and understanding of history, culture and media,” said Heidi Hennink-Kaminski, the school’s interim dean and Hugh Morton Distinguished Professor. “Trevy’s experience, research and teaching combine to deliver that powerful learning experience to students with her course on the history of the Black press.”

For McDonald, the best moments in "MEJO 342" come when her students have “a-ha” moments.

“Knowing this course gives students an appreciation of the Black press, as well as Black history, and connects those dots so that they can better understand the present — that fulfills me as a teacher,” McDonald said. “It reminds me why I love what I do.”